There’s a folk theorem in climate policy that if the public paid more attention to climate change their willingness to act would rise. By that theorem, climate policy should be surging because media coverage has been rising.

The problem is: How should we measure media coverage? If our measurements are focused on news outlets read mostly by elites, then lots of apparent media attention to climate change—and the need for action on climate change—could be misleading. Elite America, such as policymakers and business executives, might be paying close attention to climate while the rest of the country is a lot less engaged. If such a gap exists—or is growing—then care is needed to make sure that climate policy is framed in terms that the bulk of the country finds attractive. Indeed, many policy studies (e.g., this one from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences) have suggested that kind of framing as a way to build and sustain political support for action. But does the data support the need for that kind of framing? In short, the answer is yes.

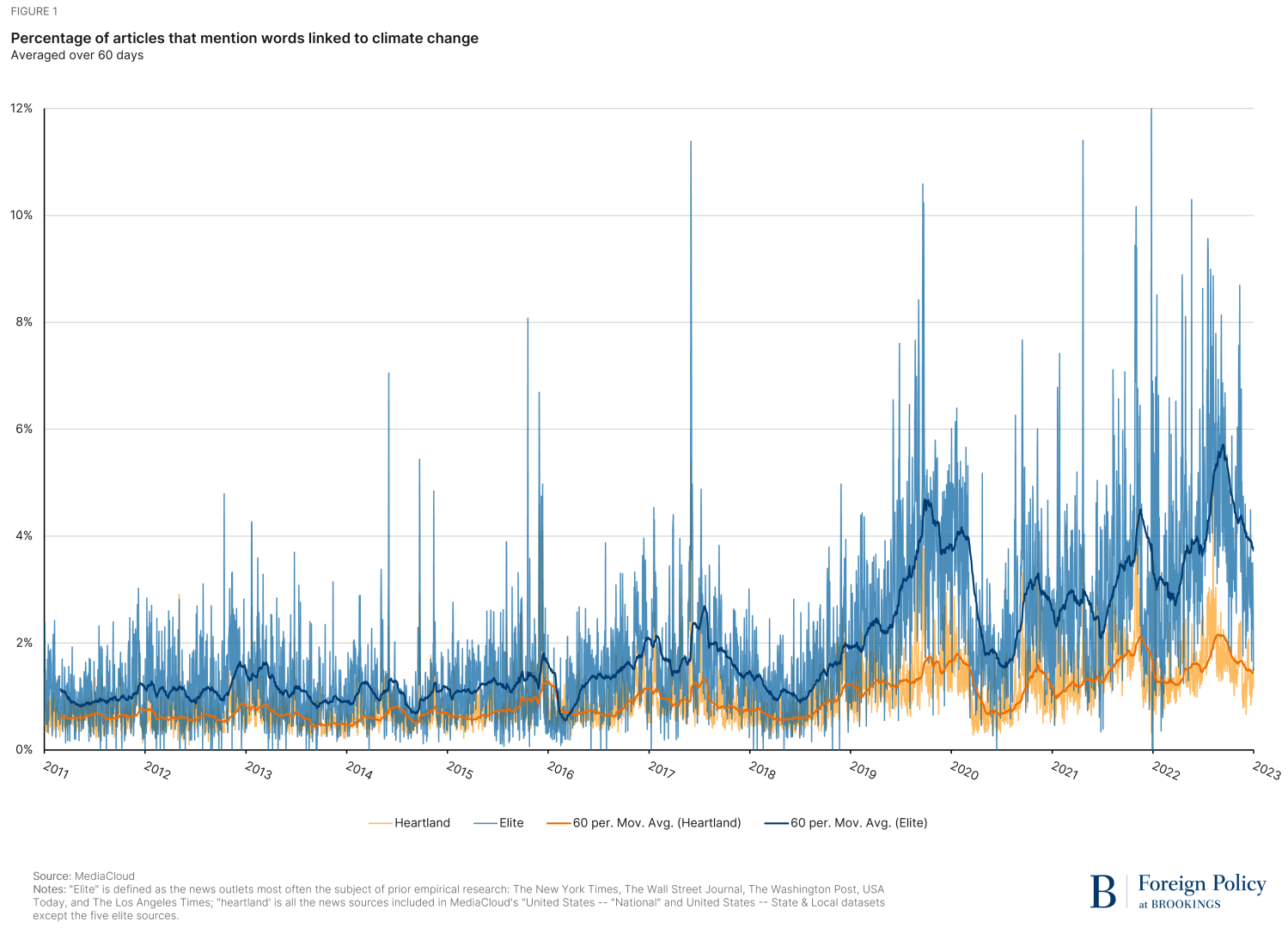

A huge literature on media coverage of climate change has tracked attention to climate change by focusing on media sources that are easy to query—the newspapers of record such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, and The Wall Street Journal. These papers have seen surging coverage of climate change—a 300% increase since 2012. The biggest increases have happened in the last five years as national newspapers, whose editorial rooms are mostly concentrated along the coasts and in metropolitan areas, expanded their climate desks and significantly increased their coverage. In contrast, smaller news outlets spread across the rest of the country—what we’ll call America’s heartland—have also increased their coverage but at about half that rate.

The figure above shows coverage of climate change in elite news outlets and the rest of American news outlets, which we call the heartland in the MediaCloud database. Following a database query method widely used in the literature, we searched on key terms—in our case: any article that uses the terms “climate change” or “global warming” or “greenhouse gas” or greenhouse effect” in their article headline or body. We define “elite” news outlets as the five most often the subject of prior empirical research: The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, USA Today, and The Los Angeles Times. Our choice of the term “Heartland” is not without flaws. It includes papers ranging from the Stamford Advocate to the Boston Globe. It also includes the Des Moines Register, the Bozeman Daily Chronicle, and the Fort Bliss Bugle. It’s a big category that, numerically, is dominated by papers designed for state and especially local coverage.

Trends in elite and heartland coverage

In June, we published a peer-reviewed paper that documented these patterns. Our motivation was a concern that climate change reporting occurred in an echo chamber. There are well-known divisions between how Democrats and Republicans pay attention to climate change—along with big divides in how much they worry about the lack of action to protect the climate. And several studies, including Benji Backer’s recent “The Conservative Environmentalist,” point anecdotally to an urban-rural divide.

Our study puts numbers on these trends. Back in 2011 when our data sets began, the difference between elite and heartland news sources’ coverage of climate change wasn’t that big. On any given day in 2011, there was a 30% chance that heartland news outlets would cover climate change more than elite newspapers. As the two domains of news diverged, however, so did those probabilities. By 2022, the odds that heartland news outlets would cover climate more than elites on any given day had plummeted to about 3%.

To do this work, we took advantage of a stunning database that aims to cover all of America’s news outlets—MediaCloud. Originally part of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and now at Northeastern University, MediaCloud has aimed to scrape the nation’s news. That turns out to be really hard, in part because so many news outlets are not as readily visible such as over the internet. Over time, MediaCloud’s database has expanded radically, which gave us statistical challenges galore as the denominator of news coverage shifted over time. (The paper and its statistical appendix work through some of the different ways to analyze the data.)

The databases we used included, by 2022, more than 25 million articles every year. (The volume of articles queried increased by a factor of 10 since 2012.) Nearly all queried articles were from state and local sources. Indeed, the national elite news outlets accounted for just a tiny, 0.6%, percent of the total media coverage studied in 2022. (One challenge in our analysis is the reprinting of stories, including through wire sources, but our methods can’t disentangle that yet.)

Last year, we reported through Brookings the good news: the public is paying more attention to climate change. What’s new with this academic study, however, is the detailed comparison between what the average American sees in news outlets and what those who rely on elite news media are seeing.

This work has a few big implications.

Implications and media and politics

One is a reminder for researchers studying the role that media plays in informing the public about pressing global issues: they need to look at all sources of news, not just the major outlets like The New York Times and The Washington Post. It also serves to remind us, as climate-policy wonks, that we need to pay particular attention to how different parts of American society get their news. In this study, we focused on coverage in non-elite news outlets—most of which are local—but additional work is needed to focus on the wider array of information outlets that shape public opinions and political behavior like voting.

Another implication is political. Public concern about climate change rises and falls—in part with the cadence of other issues on the public mind. This election year, recent Gallup polling found that concerns about the environment (including climate change) are at No. 12 on a list of 14 possible policy priorities.1

A durable strategy for action on climate change will depend on many factors, but central is the ability to sustain a broad and durable political coalition in favor of action. A logical extension of this argument, implicated by our study, is that it remains extremely important to link climate change to other actions that local communities care about, such as improving resilience, generating employment, and reducing local air pollution. In time, the broad public may become so concerned about climate change that the nation will be able to adopt policies, such as carbon taxes, that most analysts love but tend to carry a lot of political baggage.

The good news is that there are many places where the goal of less global warming links to policy priorities that aren’t just of interest to national elites or to one political party. Among them is the deployment of renewable power, which polls well with most democrats and many republicans. Energy security—which a smart climate policy strategy can advance as well—also polls well with most republicans and many democrats. And the protection and conservation of wilderness areas from pollution and oil and gas development—which also polls reasonably well across both parties.

Our earlier research suggests that one of the places where all Americans will quickly see the importance of action on climate change concerns its physical effects. The country is exposed to climate impacts—republican counties even more than democratic ones. And the really big exposures will be felt as insurers begin to reprice coverage. Already the federal government has done that for flood insurance—which carries its own hazard of encouraging people to build or remain in areas at high risk of flooding. In time, crop insurance faces serious risks of rising premiums, depending on how climate impacts and insurance policies unfold. Folks affected by hurricanes—which cause wind and flood damage—are already seeing big changes, and the best modeling studies suggest more are afoot.

All these topics will affect the whole of the country—especially the heartland. They are ripe for more media coverage that links climate to what average Americans care about. And in doing that they can shift the politics of climate change to one that engages the whole country.

-

Footnotes

- In the longer paper on which this blog is based, we looked into the content of elite and heartland coverage and found differences in which articles gained the most attention. Both kinds of news outlets covered the biggest climate stories like the Paris Agreement or President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from that agreement. Elite outlets tended to focus more on international diplomatic events while heartland news outlets gave more attention to the pope’s statement on the environment, for example. But the data is finicky to work with and sensitive to methods; future work should focus more on content—probably using full-text analysis rather than keyword searches.

Commentary

The growing divide in media coverage of climate change

July 24, 2024